Breaking the Silence

A Suicide Prevention Program for Faith Communities

Program Overview

“Breaking the Silence” is a four-part suicide prevention program for faith communities:

- Preaching - Faith leaders preach on suicide and co-occurring mental health conditions such as depression or substance abuse.

- Training - Congregation members participate in our 1-hour suicide prevention workshop, learning about what can cause a someone to become suicidal and how to identify and help a suicidal person.

- Asking - When going to doctor’s appointments and other healthcare settings, congregation members ask to be screened for depression.

- Nurturing - Congregations become active in raising awareness and taking next steps to promote mental health care in their communities.

Our page is intended to provide faith communities with ideas and resources for implementing a suicide prevention program. First, we provide scripture suggestions and sample sermons along with web links to additional materials. Second, we also include a download of this suicide prevention training workshop and discussion guide. Third, we give a description of common depression screening questions and why it is important that health care providers screen for depression. Fourth, we offer a range of goods that congregations can either sell or give to their members, such as display posters and car magnets that read “Stop Suicide: Talk Saves Lives”. Displaying these goods not only helps raise awareness, their sale can also be used as a vehicle to fund additional ministry activities. Lastly, we offer suggestions and links to additional materials that faith communities can use to grow and sustain a mental health ministry.

About SPM

The Suicide Prevention Ministry is a grassroots 501(c)(3) organization and an Independent Lutheran Organization of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America that is powered largely by people who have lost a loved one to suicide. Based out of the ELCA Southeastern Synod in Atlanta, SPM performs the tasks necessary to engage the ELCA, interfaith communities, and the private and governmental suicide prevention organizations with a vested interest in including faith communities in suicide prevention work. SPM has a credible record of empowering survivors of suicide to achieve highly significant national goals in suicide prevention work and was a founding participant in crafting the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention.

Background: Research and Statistics

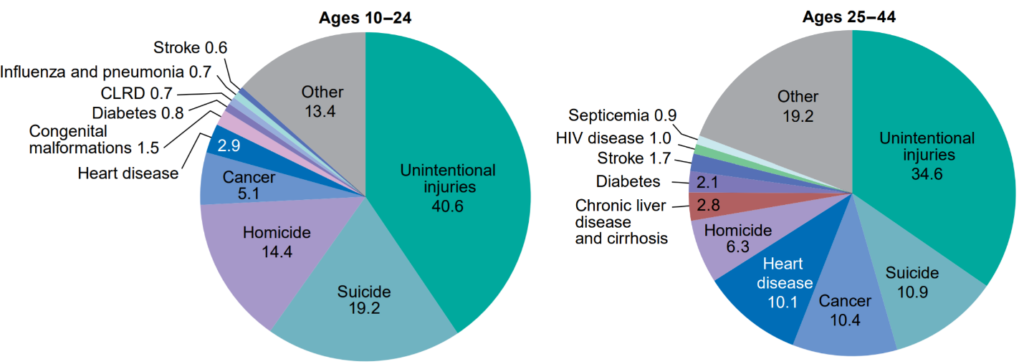

Suicide, the intentional killing of one’s self, is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States. It is also the second leading cause of death for individuals ages 10 – 44:

Figure 1. Percent distribution of the 10 leading causes of death, by age group: United States, 2017.

Source: CDC National Vital Statistics Report, June 2019.

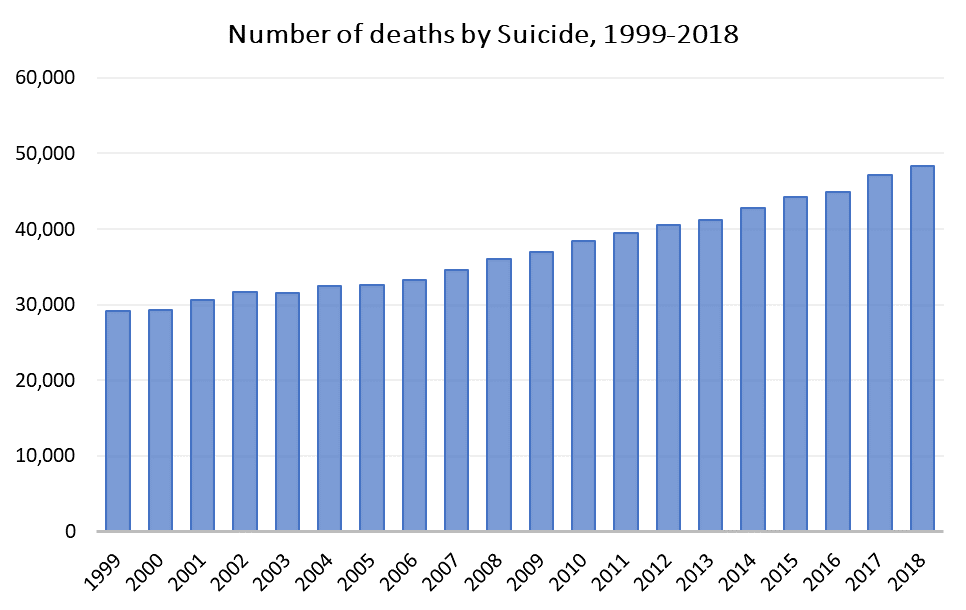

In 2018, 48,344 Americans died by suicide (132 every day), and there were an estimated 1.4 million suicide attempts – roughly 25 attempts per completed suicide. 10.3% of Americans have thought about suicide. Despite prevention efforts, the number of suicide deaths per 100,000 people has increased from 10.5 in 1999 to 14.2 in 2018. Annual number of deaths by suicide has increased 60% in a 20-year span.

Figure 2. Increase in Suicide Mortality in the United States, 1999-2018.

Source: NCHS Data Brief, April 2020.

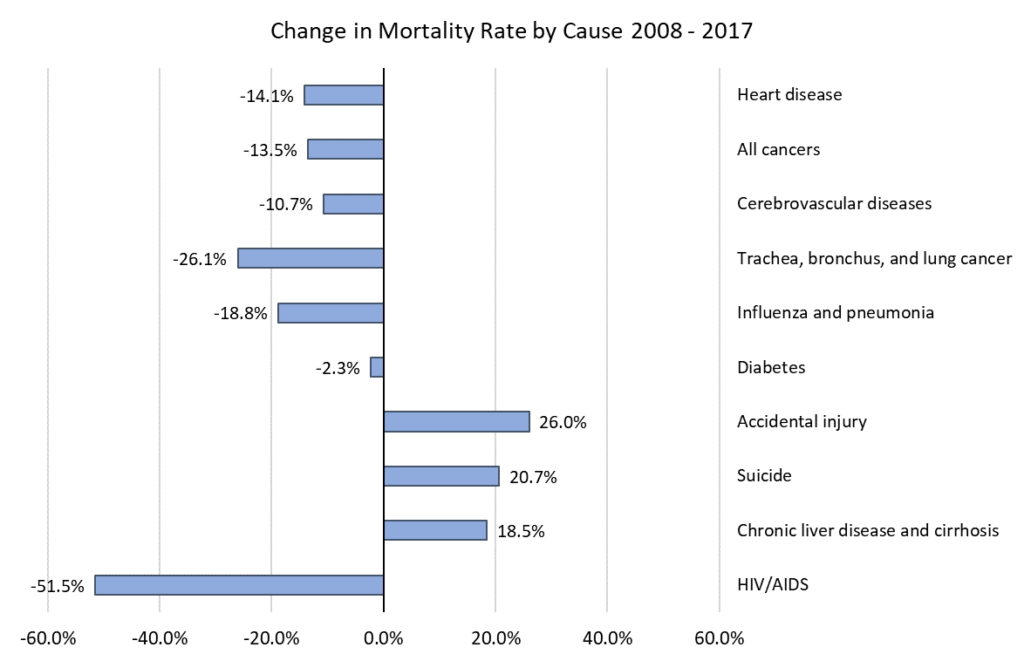

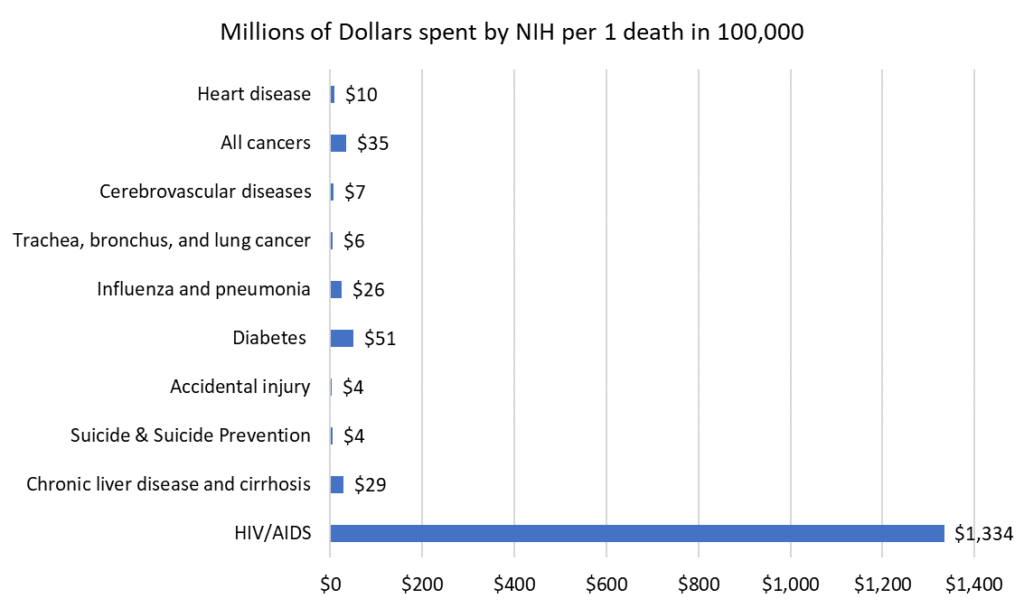

Suicide continues to take more and more lives each year. These two graphs compare the change in mortality rate by cause from 2008 to 2017, as well as the research dollars spent by the National Institutes of Health for that same time period.

Figure 3. Age-adjusted death rates per 100,000 people for prevalent causes of death, United States 2008 – 2017.

Source: CDC Data Finder, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2018.htm?search=Deaths.

Figure 4. Total NIH funding by cause divided by 10-year mortality rate, United States 2008 – 2017.

Source: CDC Data Finder, NIH Estimates of Funding for Various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories, February 2020.

Suicide and other Issues

Co-Occurring Mental Health Disorders

Suicidal thoughts affect one’s emotional and psychological well-being in a myriad of ways. Individuals with mental health conditions frequently attempt to self-medicate with alcohol or drugs, as they can provide temporary relief of emotional pain. In the long run though it can make matters worse. Studies on suicide reveal a strong correlation between suicide and substance abuse; Individuals who abuse substances are 10 to 14 times more likely to contemplate, attempt, or complete suicide.

The World Health Organization estimates that mental health conditions are associated with more than 90% of suicide cases. Mental health and substance abuse are major drivers.

Risk Factors: Note the overlap with systemic and social justice issues.

- Social isolation (perhaps the strongest predictor)

- Mental health disorders: clinical depression, anxiety, bipolar, schizophrenia, substance use disorders, compulsive disorders, eating disorders, trauma disorders

- Physical illness

- Unemployment

- Homelessness

- Minority stress (injustices, racism, low socio-economic status)

- Veteran status

- Adverse life events

- Access to firearms (accounts for more than half of all completed suicides)

- Family conflict, trauma from relationships, trauma from childhood

- Low self-esteem

- Feelings of hopelessness

- Feeling like you don’t belong

- Feeling that you are a burden on others

- Unshakeable guilt or shame

- Genetics and family history

- Grief and loss

- Brain-chemical imbalances due to medication

- Previous suicide attempts (reduced fear of death, increased pain tolerance, increased ability to self-harm with repeated attempts)

Contagion: Studies show that suicide rates increase when high profile suicides occur (such as celebrities or others prevalent in media coverage).

Impacts

- Suicide prevention organizations estimate that about 7 million people are directly impacted by a suicide (family members and closer friends); the number of those in a person’s wider social network are exponentially higher (about 54% of Americans).

- The cost of suicide was $69 billion in combined work loss and medical cost in 2015. Investments in additional counseling and medical services would provide a 6-to-1 benefit to cost ratio.

Reasons for Hope

According to an online survey conducted by The Harris Poll in August 2018,

- 94% of adults say that they would do something if someone close to them was considering suicide.

- 78% are interested in learning more about how they could play a role in helping someone who may be suicidal.

- 94% think suicide can be prevented.

- 73% would tell someone if they were having thoughts of suicide, indicating the importance of engaging in non-judgmental conversation.

- 48% of those who are suicidal and have spoken with others about suicide say it helps them feel better – indicating that talking about suicide does help.

Suicide, Mental Health, and the Church

In 2018, over 46,000 people took their own life in the United States, a mortality rate of 14.2 for every 100,000 people. According to the 2018 General Social Survey, about 40% of American adults claim to go to some religious service at least once per month, or around 100 million people. Including children and youth, the total is 130 million. Though no formal studies have been conducted on the prevalence of suicide in faith communities, we could extrapolate that 14,200 people within faith communities complete suicide every year, based on the above figures and assuming little deviation from the general population.

Indeed, not even clergy are immune to worldly ills. An alarming number of pastors have taken their own lives in recent years. An examination of deaths by profession of the National Occupational Mortality Surveillance database reveals that the prevalence of suicide among black clergy and white female clergy members is greater than the average of all occupations. The reasons are numerous and multifaceted. But despite the increase in suicides nationally, and the fact that religious beliefs alone often cannot resolve mental health concerns, many churches remain silent on the issues of suicide and mental health. Additionally, only 41% of pastors nationwide have received training to assist someone dealing with suicidal thoughts.

Suicide is one the most stigmatized of all human activities – perhaps even more stigmatized than murder or slavery. Stigma can be defined as a combination of fear and ignorance. Without knowing what to say or how to be present to those who are in distress, we act against our instincts out of fear and uncertainty. We might ignore warning signs or avoid overt appeals for help.

Traditionally, the church taught that taking one’s own life is a grave sin. Where the afterlife is concerned, many have believed that the result of suicide is an eternity separated from God. Moreover, mental illness is often seen as a sign of weak faith, and that a person simply needs to “get right with God.” Such views divide the body of Christ and border on idolatry because they glorify individual righteousness, further compounding the stigma of mental illness in faith communities. More recently, such views have been challenged on theological grounds, yielding unique opportunities for spiritual healing and religious education.

Clearly, it is critical that religious leaders and laity alike receive proper training on how to handle individual conversations about mental health and suicide, as well as how religion and spirituality can enhance our mutual care and support in an age where mental illnesses are accepted as legitimate medical issues.

Consensus Statement on Suicide and Suicide Prevention

from an Interfaith Dialogue

The following statement was adopted at the Interfaith Suicide Prevention Dialogue held March 12-13, 2008 in Rockville, Maryland. The event was sponsored by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center and was funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The participants included representatives from the Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, and Muslim faith communities.

![]()

Life is a sacred gift, and suicide is a desperate act by one who views life as intolerable. Such self-destruction is never condoned, but faith communities increasingly support, rather than condemn, the person who contemplates or engages in suicidal behavior. They acknowledge that mental and substance use disorders, along with myriad life stressors, contribute significantly to the risk of suicide. And they reach out compassionately to the person who attempts suicide, and to the families and friends who have been touched by suicide or suicide attempt. This increasingly charitable understanding finds agreement between the historic precepts of faith and a contemporary understanding of illness and health. It renders no longer appropriate the practice of harshly judging those who have attempted or died by suicide.

Life is a complex journey viewed through different lenses by different faith groups. But the varied eyes of all our traditions increasingly see the great potential of people of faith to prevent the tragedy of suicide. Spiritual leaders and faith communities, and now the research community, know that practices of faith and spirituality can promote healthy living and provide pathways through human suffering, be it mental, emotional, spiritual, or physical.

Faith communities can work to prevent suicide simply by enhancing many of the activities that are already central to their very nature. They already foster cultures and norms that are life-preserving. By providing perspective and social support to their members and the broader community, they compassionately help people navigate the great struggles of life and find a sustainable sense of hope, meaning, purpose, and even joy in life.

The time is right for the life-enhancing strengths that are the foundations of our most ancient faith traditions to find application in preventing suffering and loss from suicide. Suicide prevention will take a quantum leap forward as members of faith communities gain understanding and the necessary, culturally competent skills to minister to people and communities at heightened risk for suicide and to support the healing of those who have either struggled with suicide themselves or survived the suicide of someone they love.

From the ELCA Social Message on Suicide Prevention,

Adopted by the Church Council on November 14, 1999

“The Church,” Martin Luther once wrote, “is the inn and the infirmary for those who are sick and in need of being made well.” Luther’s image of the Church as a hospital reminds us who we are – a community of vulnerable people in need of help; living by the hope of the Gospel, we also are a community of healing. At the same time vulnerable and healed, we are freed for a life of receiving and giving help. In the mutual bearing of burdens, we learn to be persons who are willing to ask for healing and to provide it.

Suicide testifies to life’s tragic brokenness. We believe that life is God’s good and precious gift to us, and yet life for us – ourselves and others – sometimes appears to be hell, a torment without hope. When we would prefer to ignore, reject or shy away from those who despair of life, we need to recall what we have heard: God’s boundless love in Jesus Christ will leave no one alone and abandoned… Our efforts to prevent suicide grow out of our obligation to protect and promote life, our hope in God amid suffering and adversity, and our love for our troubled neighbor.

Whoever among us experiences suicidal thoughts should know that the rest of us expect, pray, and plead for them to reach out for help. “Talk to someone. Don’t bear your hidden pain by yourself.” The notion is all-too common that one should “go it alone”: Persons are not supposed to be vulnerable, and when they are, they should conceal it and handle things on their own. In the Church, however, we admit that we share the “need of being made well.” There is not shame in having suicidal thoughts or asking for help. Indeed, when life’s difficulties and disappointments threaten to overwhelm our desire to live, we are urged and invited to talk with trusted others and draw upon their strength.

When, on the other hand, a loved one talks to us of suicide or we sense that something is seriously amiss, we are called to be our brother’s or sister’s keeper. The experience may be frightening, and we may want to deny or minimize suicidal communication. We may want to shy away because we feel unprepared to help someone with suicidal thoughts or think that we may make matters worse. Yet our responsibility is to listen, to encourage the person to talk, and to get him or her appropriate help.

With this message, the Church Council encourages members, congregations, and affiliated institutions to learn more about suicide and its prevention in their communities, to ask what they can do, and to work with others to prevent suicide… The Church Council urges synods to support [them] in their efforts. It directs the governing bodies of churchwide unites to evaluate their programs in light of this message, calling upon the church’s educational and advocacy programs to make suicide prevention an important concern in their ministries.